Element 1 Deep Knowledge#

From Evidence L1-E1 to L1-E5, the multilingual exploration task during classwork means that languages genuinely become useful real-world cognitive resources in meaning construction. In discussing each concept’s representation in different scripts and linguistic systems, participants categorize the semantic pattern lauding the relative representational values of ways of speaking within culture and realize that what one calls “family” means for languages. This does involve deep learning, wherein one goes beyond recalling the many family terms. It also involves the conceptual relationships that exist among such terms. Equally, for example, during discussion after lessons 1 Evidence L1-E8 to L1-E10, students enjoyed similarities in origin characters and felt competent in explaining why Japanese calls for the kanji-and-hiragana-named terms from families. So evidence points to unrelated pieces of relational knowledge.

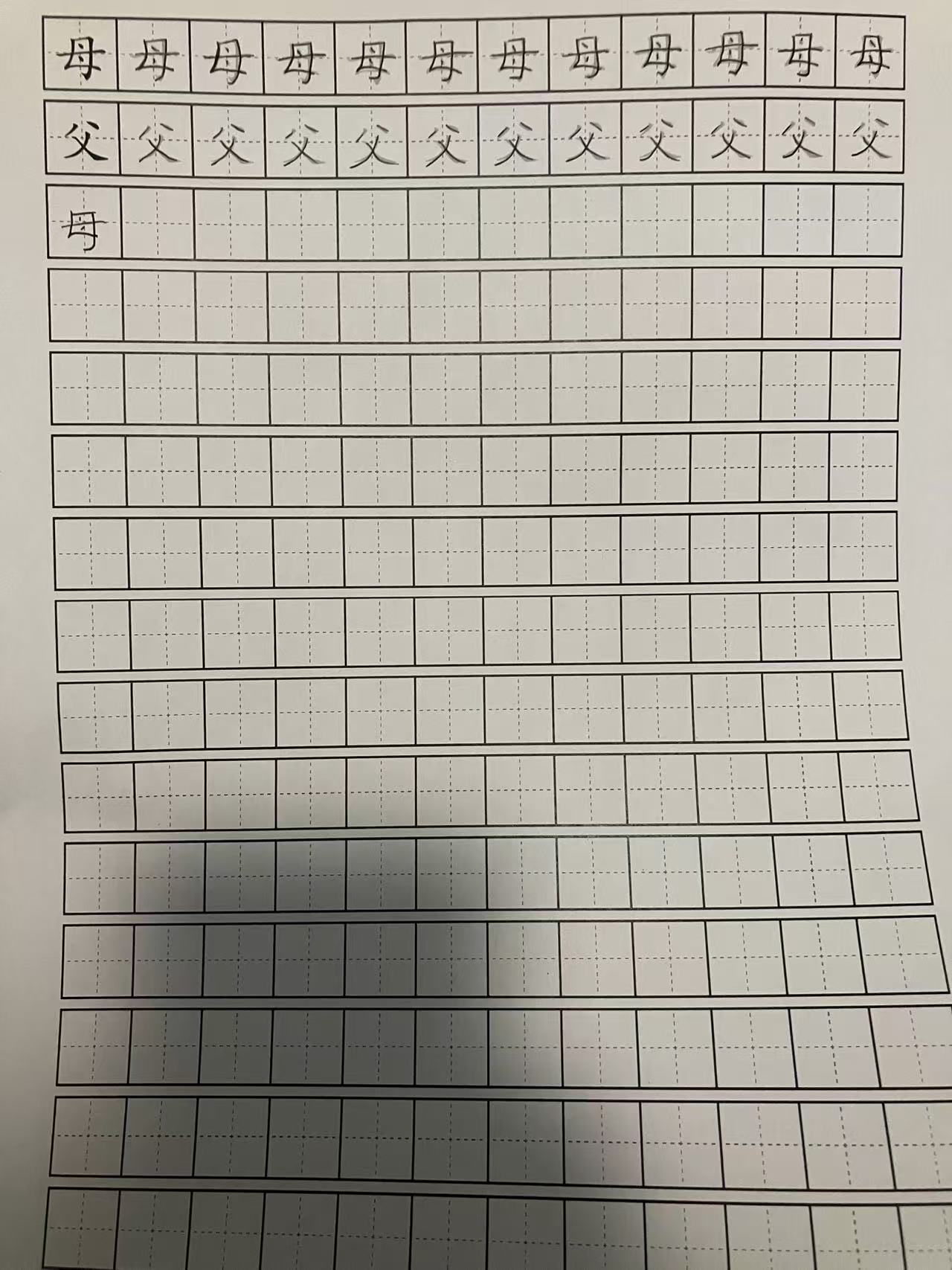

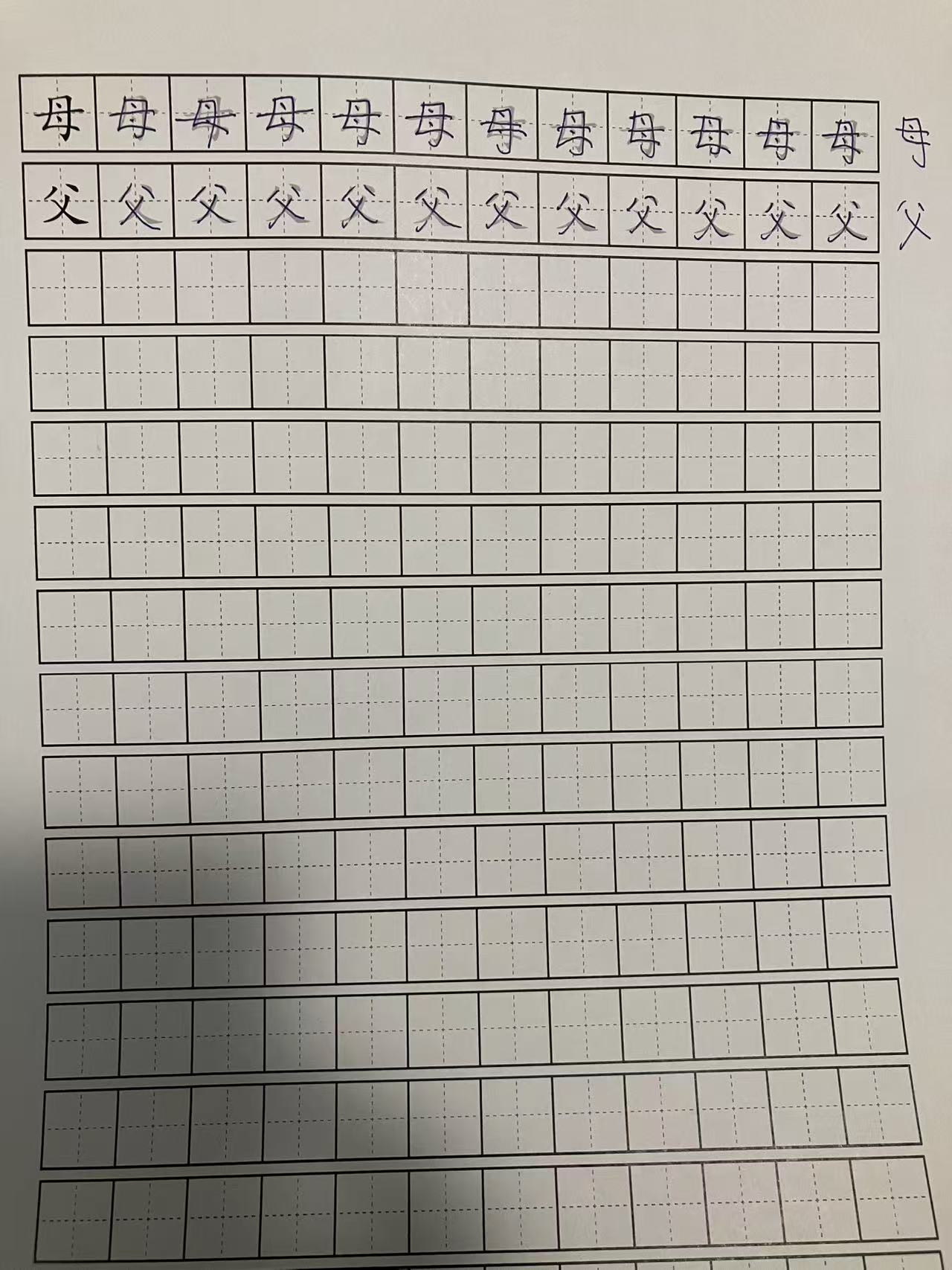

Evidence L3-V1 teach children how to conceptualize the system of Japanese writing through kanji, for instance, by disassembling 母と父, describing the components, and linking this to oracle bone script. It causes students to think peripherally about the reasons for such a form and not partly imitate form. Embedded presentation items, L3-E2 through L3-E4; The student developed form-making sense based on balance not measured per given element but rather on principles and logic of writing stokes. Form is associated with meaning and history for long-term retention and transfer, according to (Edutopia, 2022).

Lesson 2 Mystery Box L2-V1 practically tested deep knowledge without preparing for unfamiliar uses of vocabulary: retrieving words from memory would have been impossible; instead, learners were asked to postulate meanings, give reasons, and confront others with arguments. This type of language generation requires elaborated conceptual thinking, as knowledge is built rather than reproduced. According to several peer reviews in lessons 2, Evidence L2-E2 to L2-E4, the students took the task seriously and admitted that they could better remember the words that students thought aloud.

Nevertheless, developing note-making, introduced perhaps through graphic organizers, would allow ideas about linguistic patterns to be externalized and thus increase, however minimally, access to deep knowledge; Such a move would have allowed one to work on the concept of this idea already developed in the previous lesson.

Element 2 Substantive Communication#

Substantive communication requires students to engage in sustained discussion, justification of ideas, and meaningful exchange of reasoning. Across the four lessons, I purposefully designed tasks that moved students beyond short recall responses toward extended interaction, interpretation, and negotiation of meaning. The Mystery Box interaction in L2-V1 created one of the clearest opportunities for substantive communication. Students were prompted to make predictions, justify their thinking, and respond to others’ interpretations using newly learned Japanese vocabulary. Because students had to articulate why a clue pointed to a specific family member, they engaged in reasoning-based talk rather than naming isolated words. Peer feedback L2-E2 to L2-E4 confirmed that students valued the opportunity to “explain thinking out loud” and to build on each other’s responses. This aligns with the principle that dialogic exchanges deepen comprehension and conceptual retention (Columbia CTL, 2022).

This kind of exchange could have been possible during an interview exercise in lesson 4 Evidence L4-V1, for instance, with some past and spontaneous Japanese sentences. The argument is not about speech receipt since the concept of speaking about listening to an answer and asking a question again has long fitted a substantive interaction. Work samples L4-E1 to L4-E3 show negotiated meanings due to comparative interpretative meanings and misunderstandings. Framed under (Smit, 2016), discussion improves participation and learning results.

Explicit teaching in L3-V2 also contributed to substantive communication by modelling culturally appropriate response patterns such as call-and-response routines, which allowed students to participate effectively in later dialogic tasks. Feedback sheets from Lesson 3 L3-E5 to L3-E7 indicate that students felt more confident interacting because they understood expected discourse moves. This demonstrates how explicit modelling enables deeper, more structured classroom talk.

Other substantive communication was entered directly in L3-V2 concerning model responses to cultural responses and call-and-response routines that prepared students’ active participation in further dialogic activities. The feedback sheet from L3-E5 to L3-E7 speaks to students’ confidence: “I know what moves should take place in a dialogue,” showing that explicit modeling here leads to deeper forms of talking in the classroom.

Multilingual explications can therefore take place at L1-E1 to L1-E5; this is followed by very active dialogue between the peers regarding the etymology of words and relatedness between languages-price negotiation for meaning-making processes about “family.” With that much depth, the property of substantive communication may only now be realized genuinely.

This, in turn, would further allow me to structure the discussion from the simple stem proposed, leading to the quieter students being scaffolded and participating in the class discussion with all members contributing valuable insights. That would improve equity in participation and raise the quality of such student discourse.

Evidence#

L1-E1 Multilingual “Family” Poster#

Students contributed the word “family” in their home languages, enabling cross-linguistic comparison and deeper conceptual reasoning about meaning across cultures.

L1-E2 Multilingual “Family” Poster#

L1-E3 Multilingual “Family” Poster#

L1-E4 Multilingual “Family” Poster#

L1-E5 Multilingual “Family” Poster#

L1-E8 Classroom Etiquette Poster#

Supported students in participating confidently during Lesson 1 cultural discussions, reducing anxiety and scaffolding respectful communication.

L1-E9 Classroom Etiquette Poster#

L1-E10 Classroom Etiquette Poster#

L2-V1 Mystery Box Family Game (Video)#

Students practised Japanese family vocabulary using a “mystery box” guessing game.

L2-E2 Peer Feedback Sample#

Peer noted that “explaining thinking out loud helped memory,” showing evidence of deep and substantive thinking.

L2-E3 Peer Feedback Sample#

L2-E4 Peer Feedback Sample#

L3-V1 Kanji Demonstration (Video)#

This video shows the teacher’s explicit modelling of kanji structure, demonstrating the stroke order and visual origins of 母 and 父 from ancient script to modern Japanese.

L3-E2 Student Kanji Sample#

L3-E3 Student Kanji Sample#

L3-E4 Student Kanji Sample#

L3-V2 Classroom Etiquette Explicit Teaching (Video)#

Explicit modelling of call-and-response routines helped structure later dialogic tasks and prepared students for sustained communication.

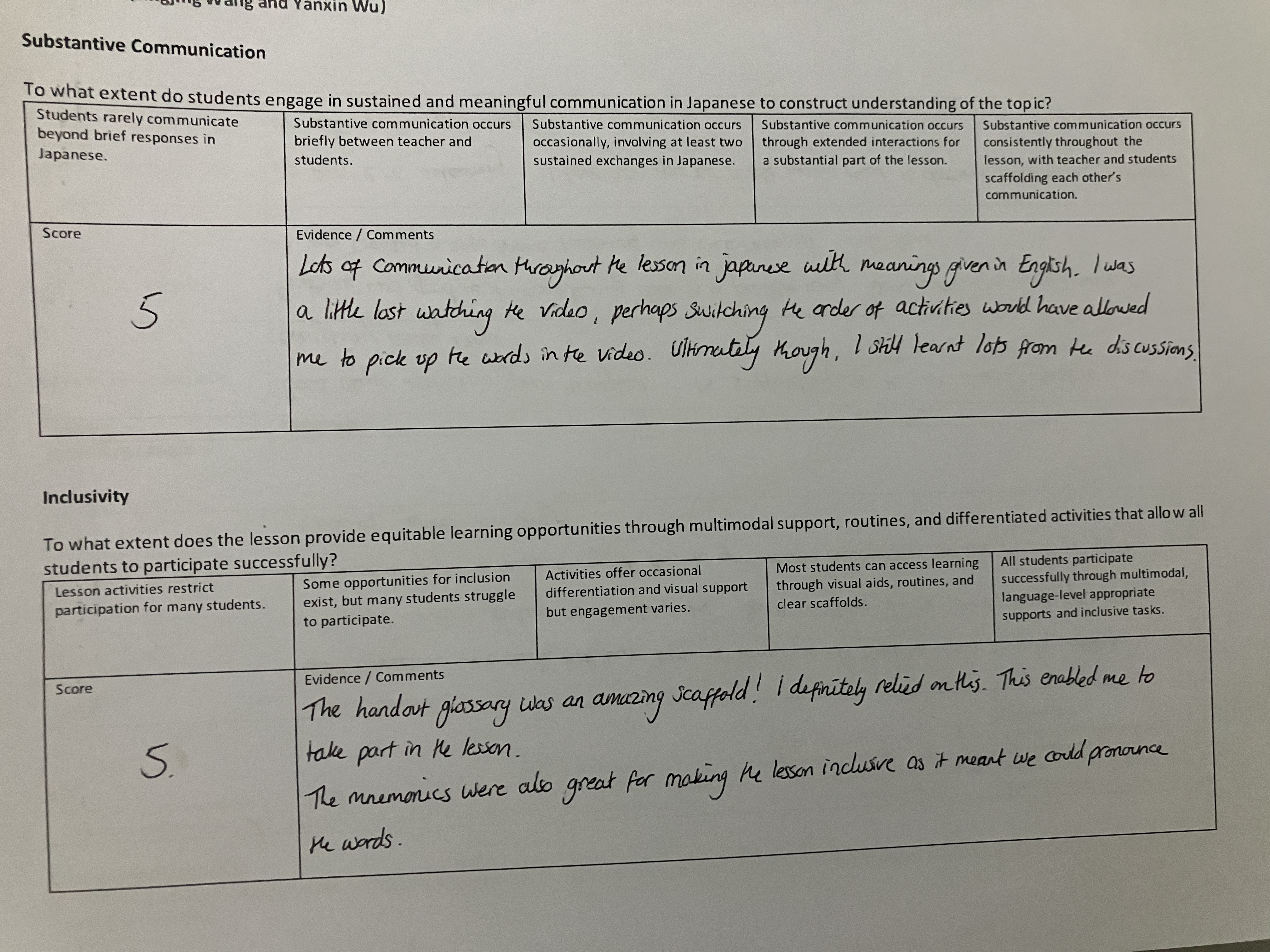

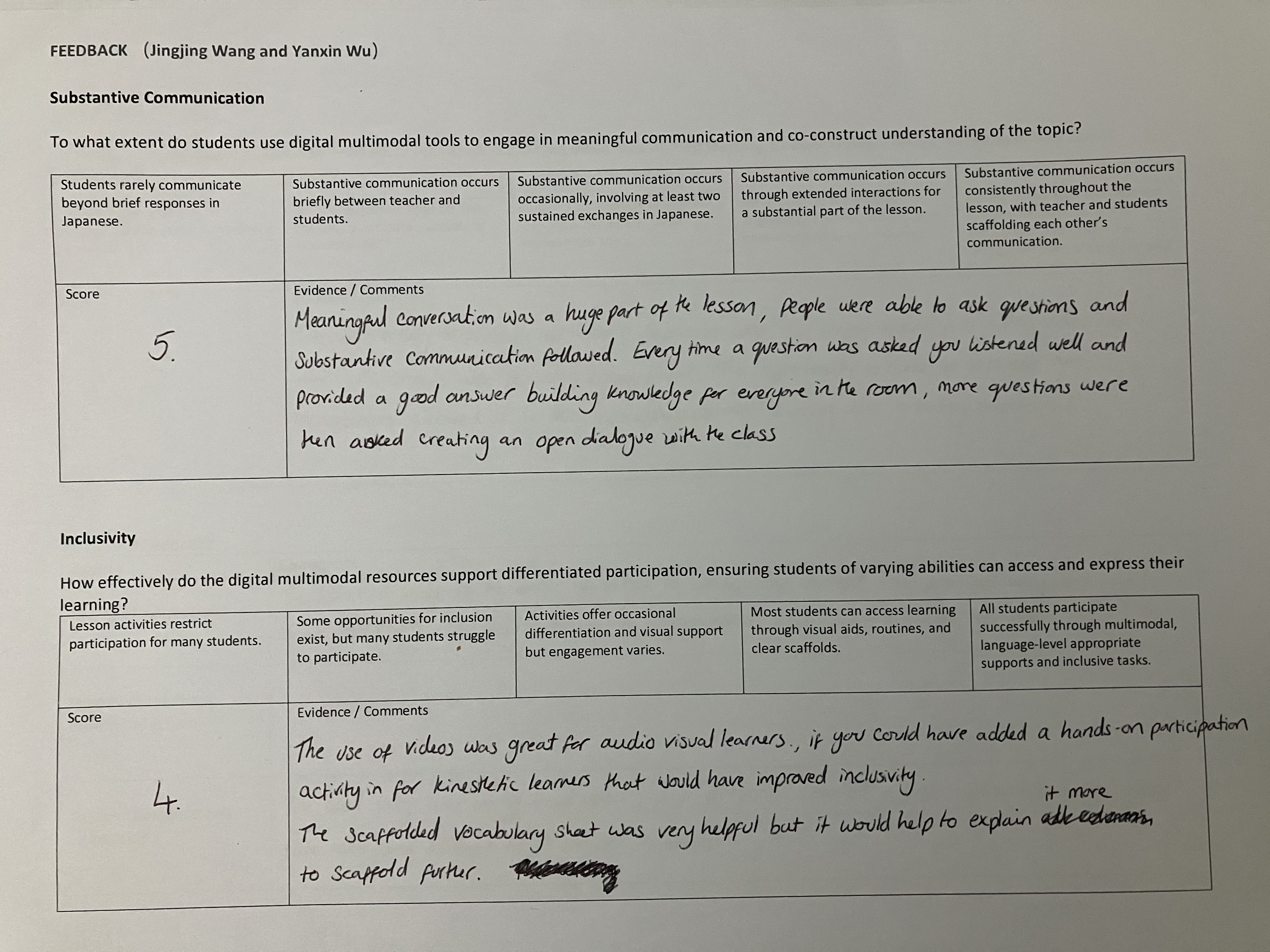

L3-E5 Student Feedback Sheet#

L3-E6 Student Feedback Sheet#

L3-E7 Student Feedback Sheet#

L4-V1 Family Interview Activity (Video)#

Introduced the Japanese 抽選器 (chūsenki) for random grouping before conducting family interviews.

L4-E1 Interview Template (Student Work)#

L4-E2 Interview Template (Student Work)#

L4-E3 Interview Template (Student Work)#